Exhibition set up at Project 107 Gallery in Toronto, 2023.

info

MATERIALS:

CONSTRUCTION WASTE, BRICK, GYPSUM CEMENT, USED AND NEW WOOD, SALVAGED INSULATION BOARD

CREATED WITH:

NICOLE CHARLES

SHOWS / FEATURES / ARTICLES:

2023 "NOTICE: A CHANGE IS PROPOSED" EXHIBITION / PROJECT 107 GALLERY IN TORONTO, ON

2023 ACOTO HERITAGE AND HOUSING SYMPOSIUM EXHIBIT AND TALK / ONTARIO SCIENCE CENTER IN TORONTO, ON

2023 THE TORONTO STAR / ARTICLE BY ROSIE DIMANNO

2023 NEW YORK REVIEW OF ARCHITECTURE / ARTICLE BY SEBASTIÁN LÓPEZ CARDOZO

Description

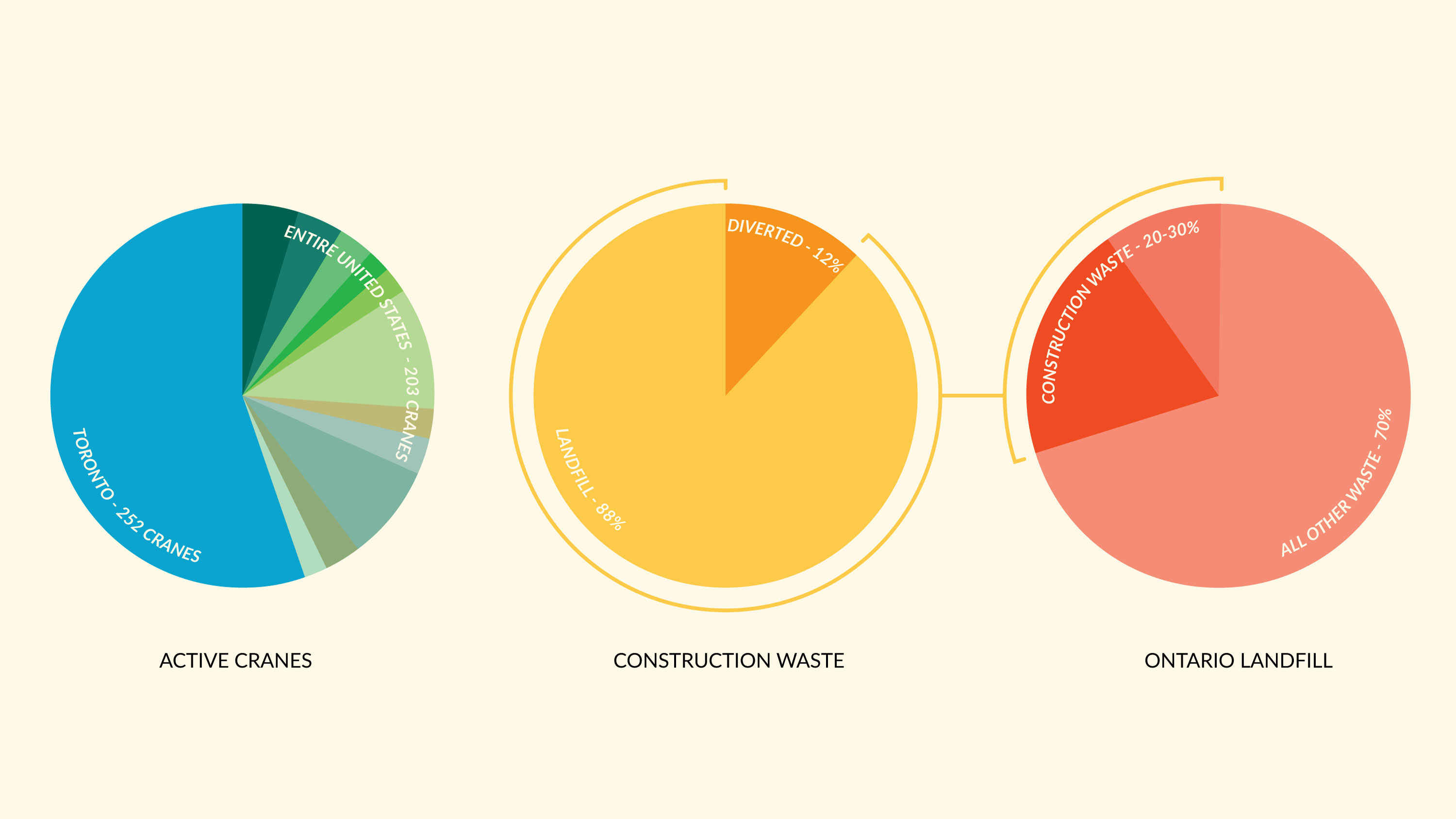

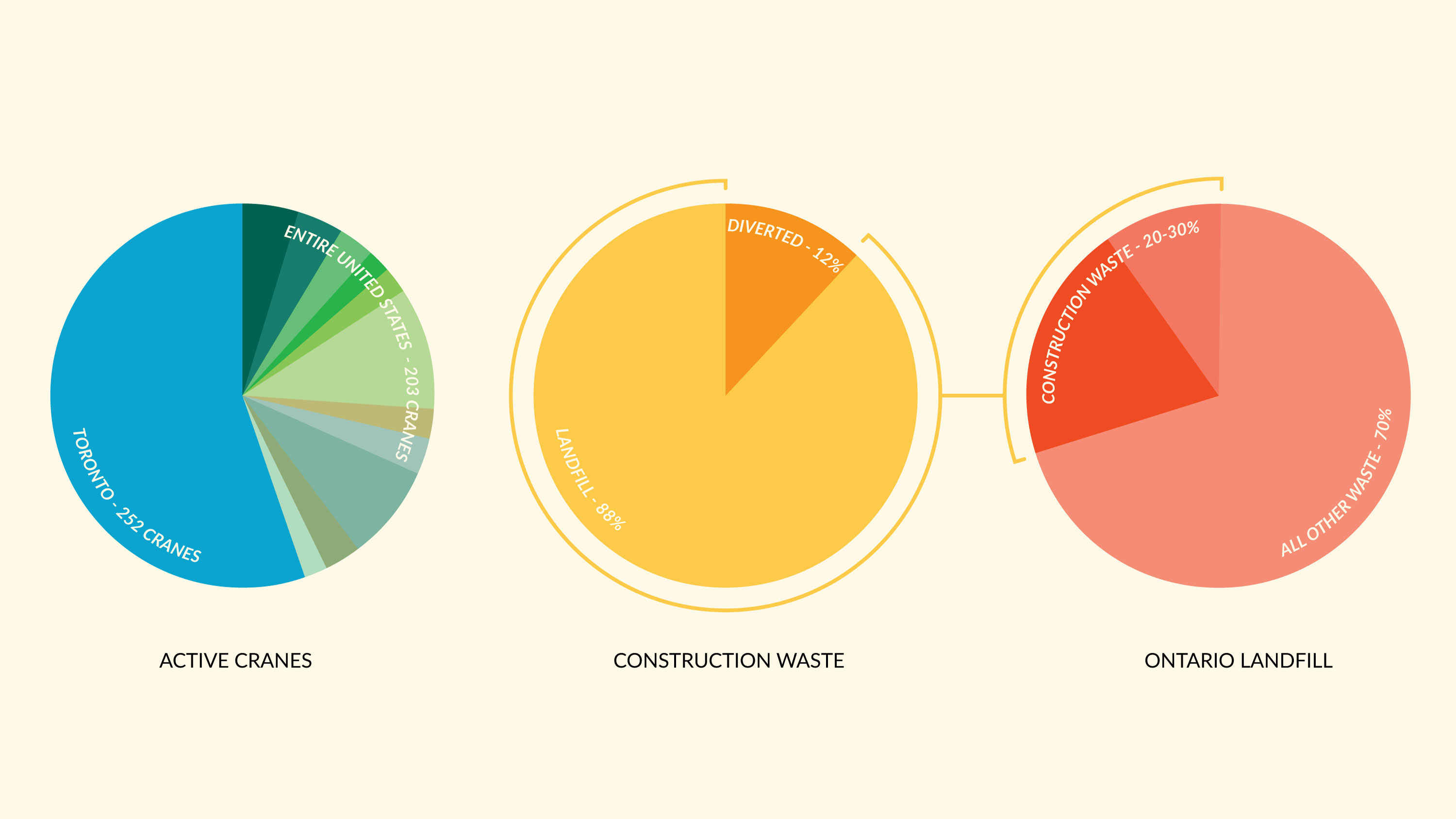

Commuting across the city of Toronto, one can notice its changing landscape – construction is a constant and cranes dress the horizon. As of 2022, Toronto was home to 252 active cranes (dwarfing the 203 active cranes across the United States), and the majority of these were used for new builds rather than retrofitting older structures. According to heritage architect Catherine Nasmith, “it takes about 50 years of energy savings to pay down the debt to the environment created by the creation and transportation of construction materials”. On top of that, only 12% of waste from construction sites is diverted from landfill. The remaining 88% overwhelms landfills and accounts for 20–30% of the total municipal landfill in Ontario. A frightening prospect is that Ontario is expected to exceed its landfill capacity by 2032.

This building, 7 Labatt Ave, has lived a life longer than most of Toronto’s inhabitants. Over 110 years it has morphed with its tenants and now, it's slated for demolition. This exhibition is an ode to the building and others like it, an exploration of the impact of construction in this city and the value we place on overlooked and discarded things. What would Toronto look like if we opted to retrofit buildings before demolishing them? How could our value system shift to appreciate the unique heritage of the city?

Stats pertaining to the construction industry in Toronto

Exhibit

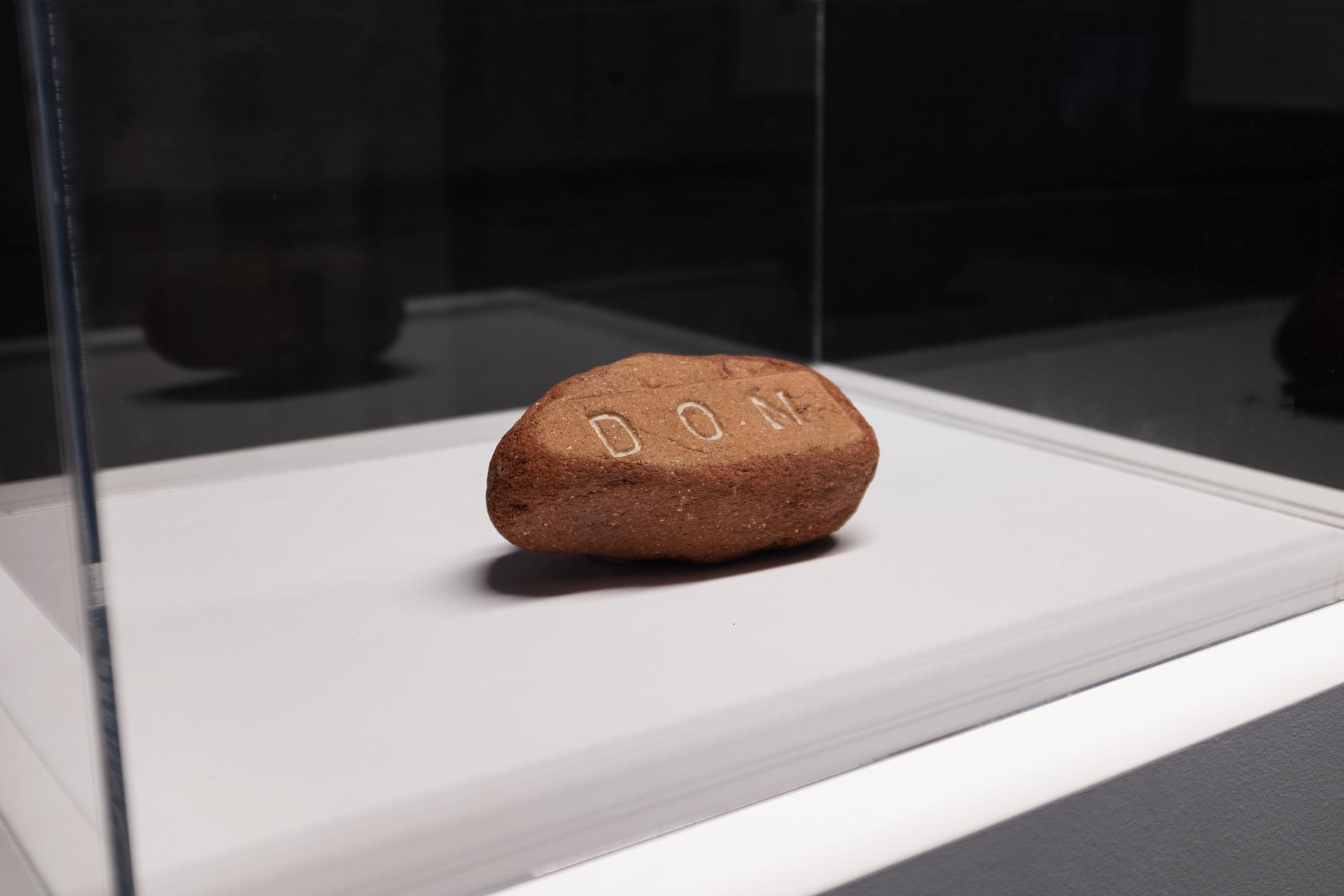

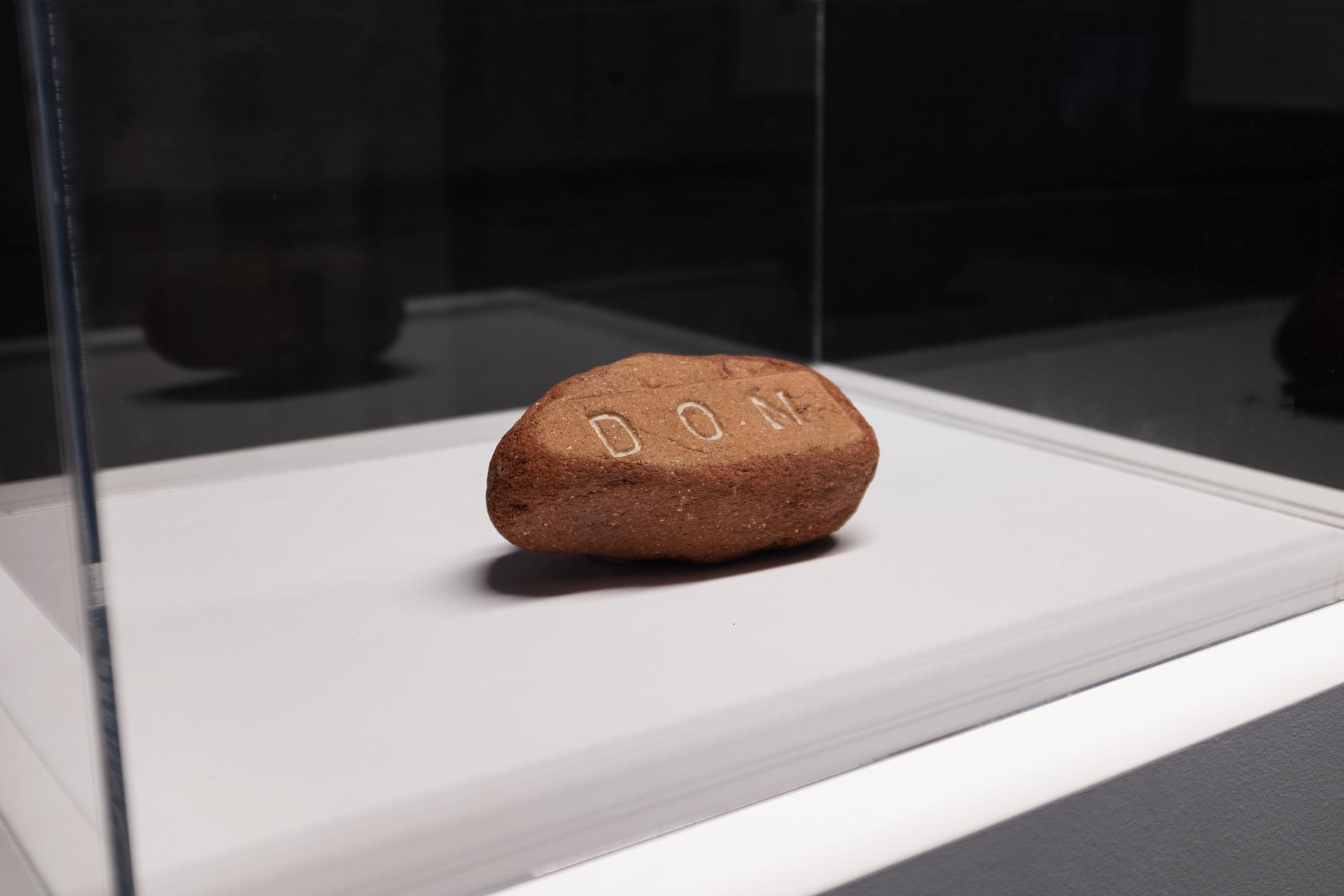

The artifacts in this exhibition are cast with a mixture of 50–75% collected debris from construction sites around Toronto, including famous landmarks, ignored structures and Victorian houses. The binding component of the mixture is gypsum based, which is a material commonly used in the construction of drywall, plaster and sometimes cement.

The molds used to cast the structures were created from offcut insulation boards salvaged from construction sites and their shapes often dictate the final form of the sculpture. Architectural and abstract in their form, they could live in centuries past or future, in an imagined city built on the foundation of its past and quietly carrying its hidden histories within its walls.

HISTORY

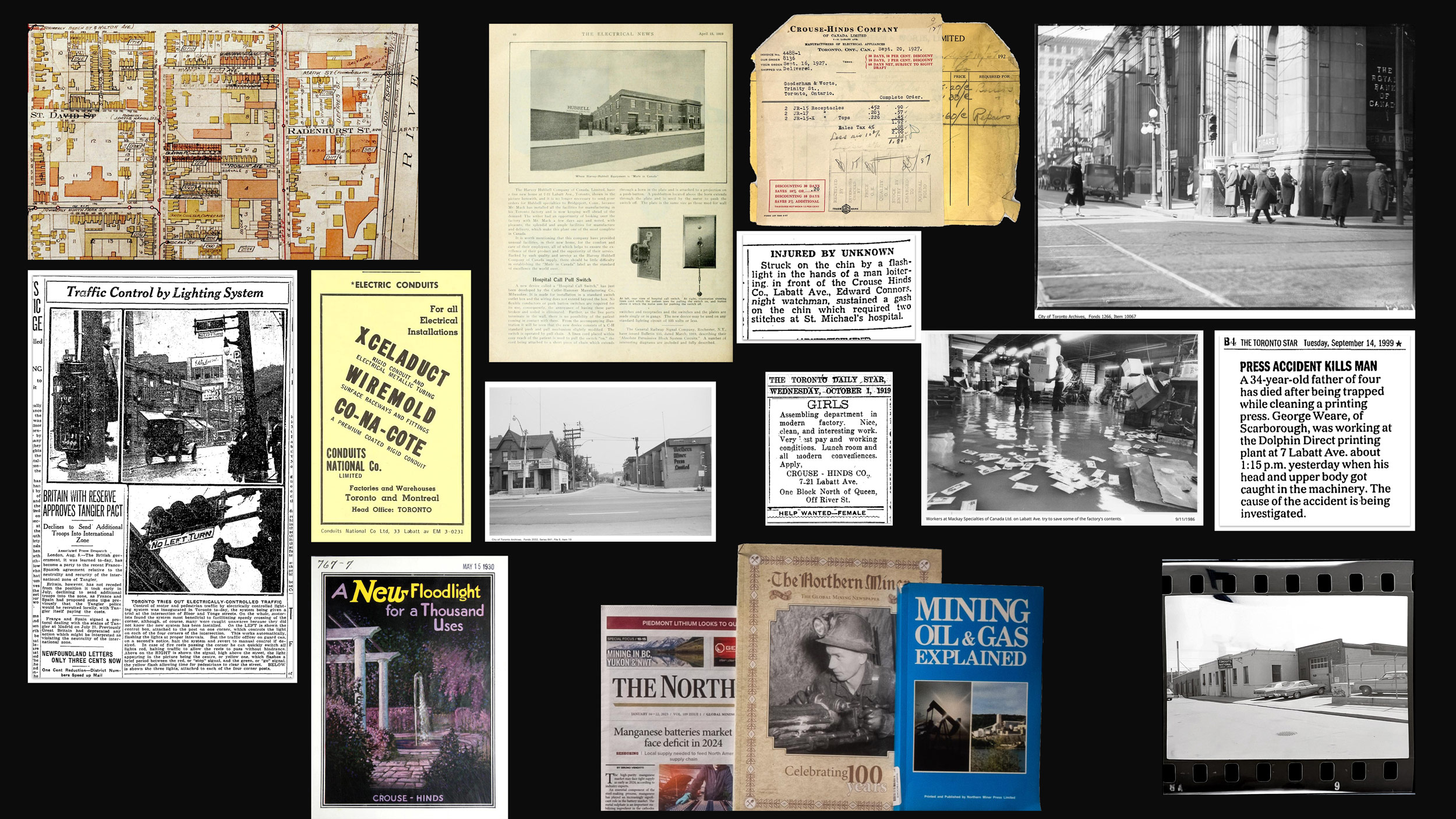

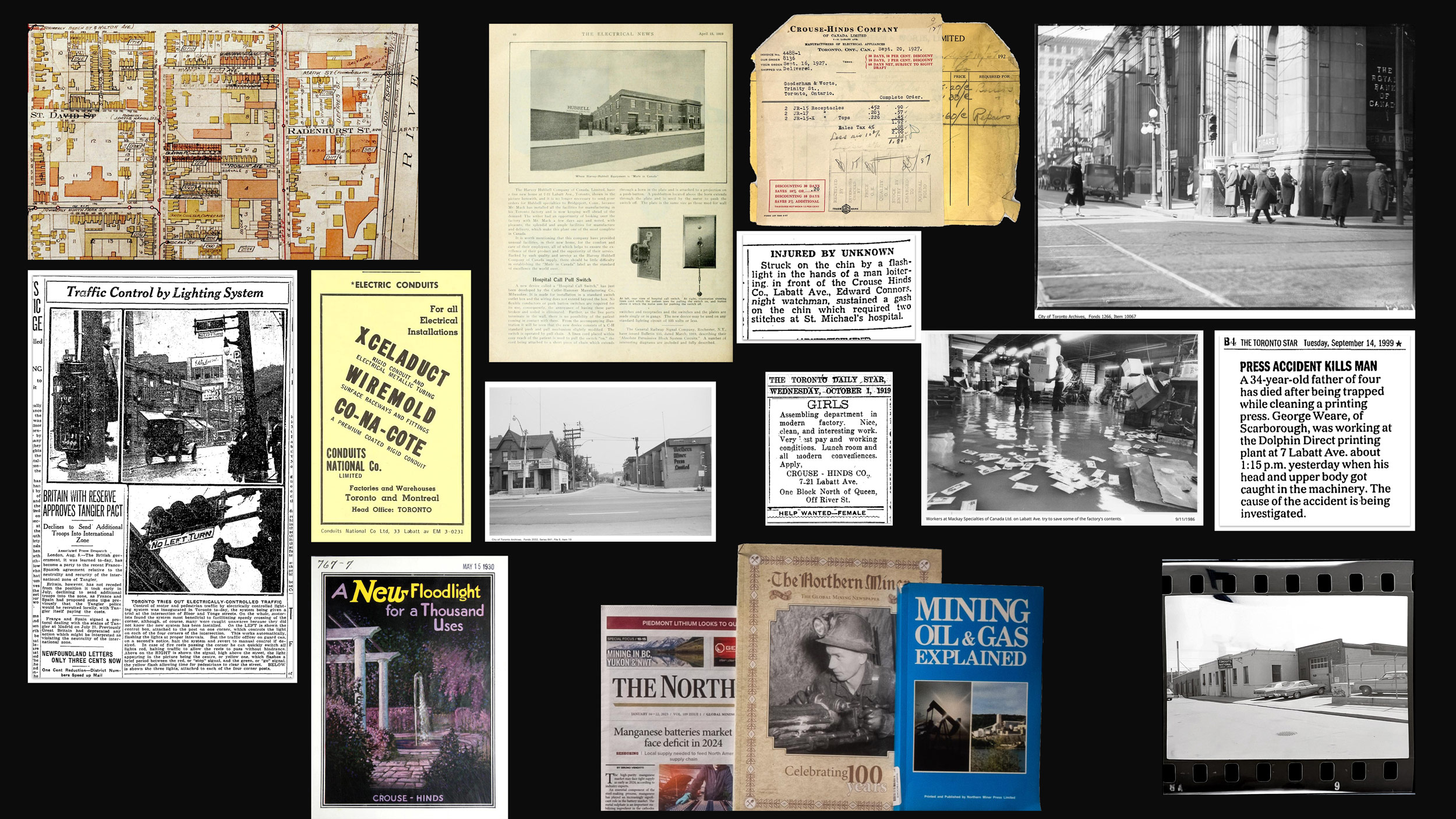

In the early 1900s, the land on which 7 Labatt Ave (formerly Radenhurst St) stands was housing. The business and manufacturing on this street began with a manufacturer of metallic conduit and interior decorations at 33 Labatt Ave. By the early 1910s, the housing was gone and a building was erected which spanned plots 11–21 Labatt Ave. (This building was the original structure of the current 7 Labatt Ave). At the time the original structure was built, the John Labatt Brewing Company had expanded its operations to Toronto and this building was the site of one of its bottling plants.

By 1917, the building had expanded from plots 11–21 to 7–21. In 1917, the Crouse-Hinds Company, manufacturers of electrical specialities, signed a lease with John Labatt Limited to rent plots 7–21 for $458.33 per month. Crouse-Hinds left the building in the mid 1960s, making them one of the longest term tenants of the building’s history.

In the 1920s, the company specialized in industrial lighting and traffic signals and in 1925, they manufactured and installed Toronto’s first traffic light at Yonge and Bloor.

According to research and records, 7 Labatt Ave was vacant from 1992–1994. Presumably this was for renovation to launch 7 Labatt Place in 1995, a community of professional, business-minded individuals.

In 2013, Labatt Urban Village was announced to replace the current building. It would be a 413 foot-high building atop an 11 storey podium.

Images, newspaper clippings, books and other historical items.

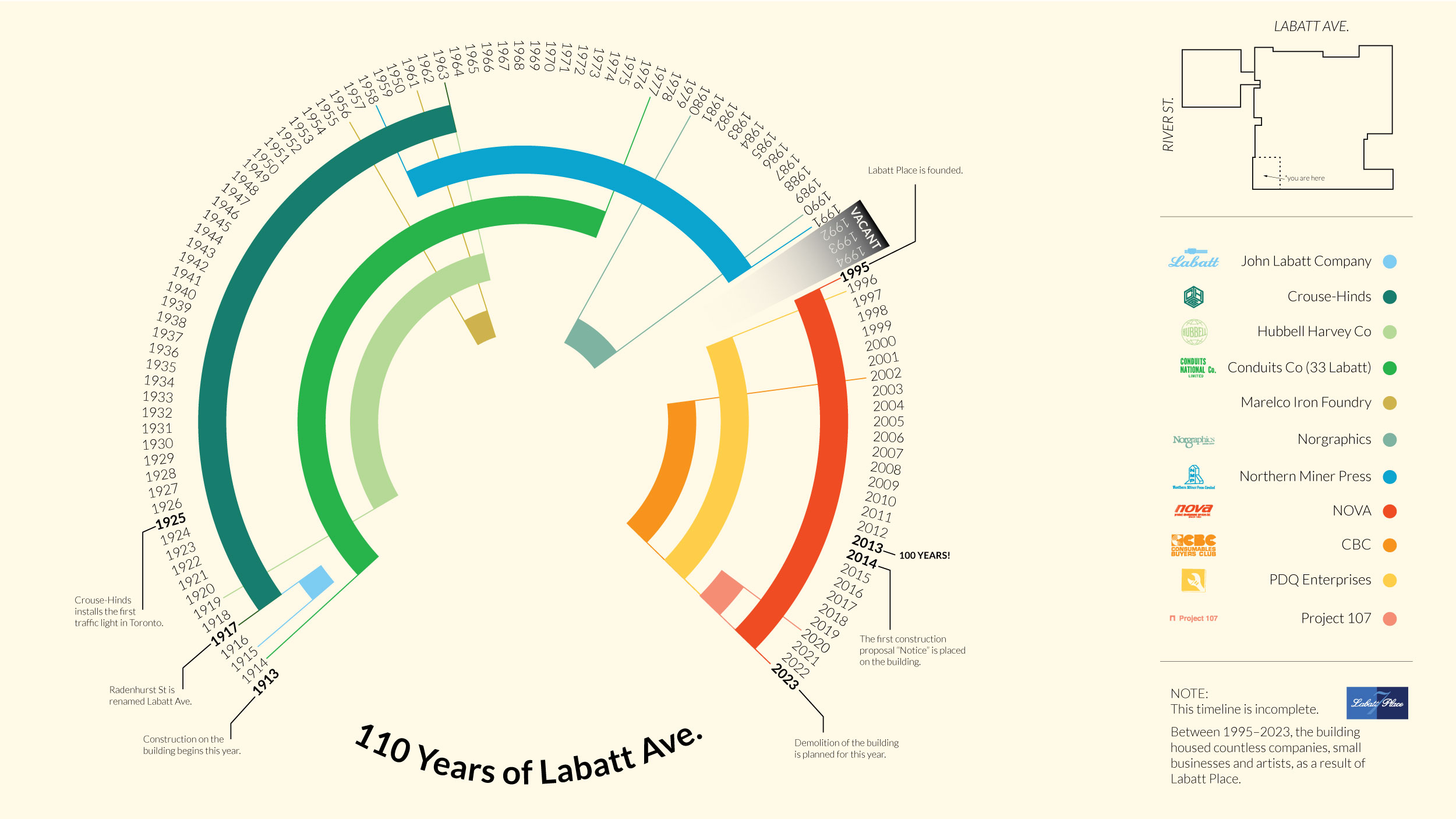

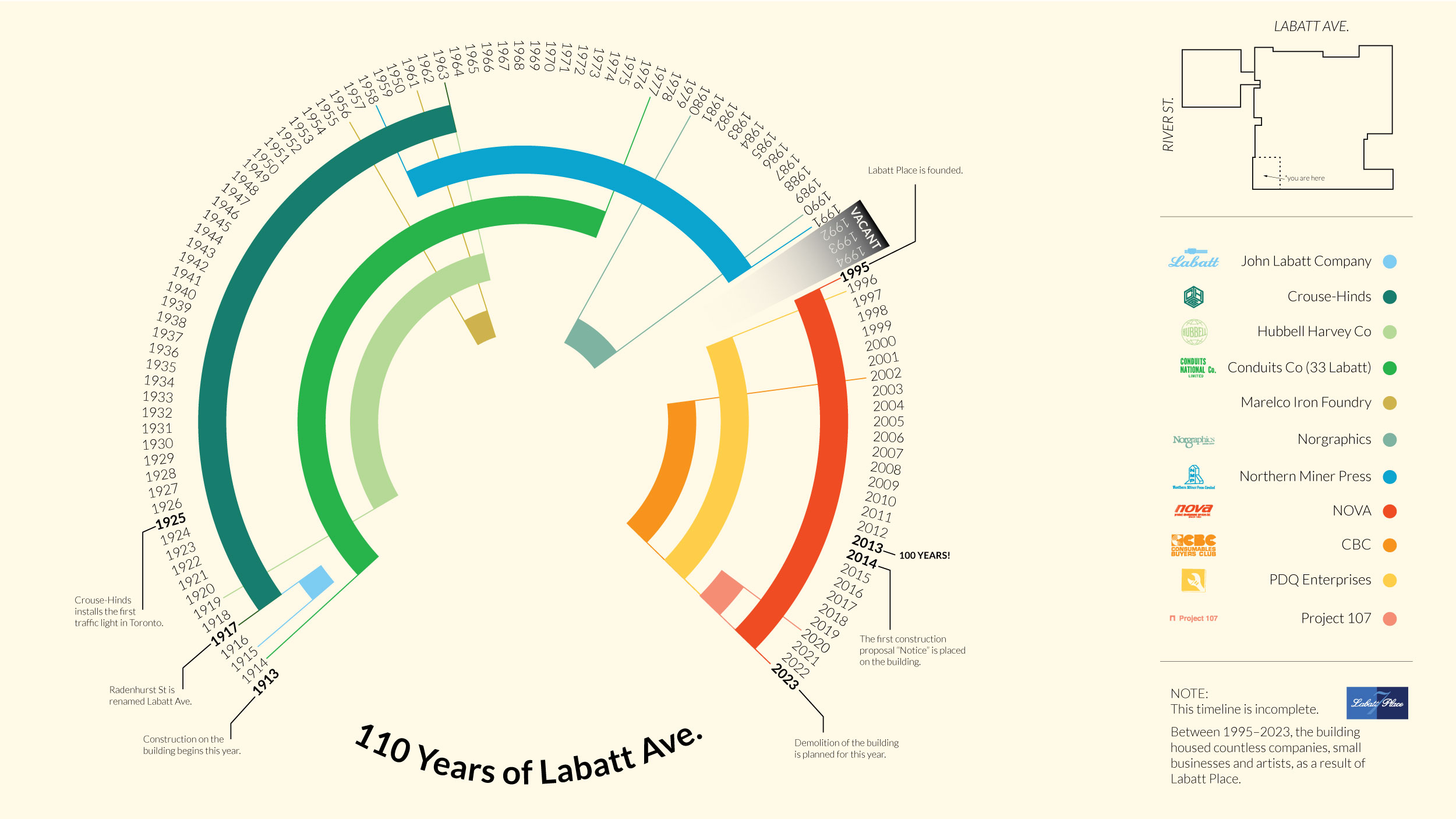

Timeline of the 110 year history of tenants in the building.

experience

The exhibit featured 3 die-cast and green enamel explosion proof lights that were manufactured in this building by the Crouse-Hinds company while their factory was in the building.

The sound playing throughout the exhibit was an abstracted drone I made from a recording of a construction site. s

ontario science centre

As part of the Architectural Conservancy of Ontario's annual symposium, the exhibit was displayed at the historic Ontario Science Centre. The centre was built by Japanese Canadian architect Raymond Moriyama, and as of the exhibit date, was in a state of limbo as the provinces government has proposed a plan to demolish it (more on this).

The centre is integrated into the one of the hills of the Don Valley ravine and sits 6km north of the Don Valley Brickworks, where most of the bricks used in this project were produced in the early 20th century.

Exhibition set up at Project 107 Gallery in Toronto, 2023.

info

MATERIALS:

CONSTRUCTION WASTE, BRICK, GYPSUM CEMENT, USED AND NEW WOOD, SALVAGED INSULATION BOARD

CREATED WITH:

NICOLE CHARLES

SHOWS / FEATURES / ARTICLES:

2023 "NOTICE: A CHANGE IS PROPOSED" EXHIBITION / PROJECT 107 GALLERY IN TORONTO, ON

2023 ACOTO HERITAGE AND HOUSING SYMPOSIUM EXHIBIT AND TALK / ONTARIO SCIENCE CENTER IN TORONTO, ON

2023 THE TORONTO STAR / ARTICLE BY ROSIE DIMANNO

2023 NEW YORK REVIEW OF ARCHITECTURE / ARTICLE BY SEBASTIÁN LÓPEZ CARDOZO

Description

Commuting across the city of Toronto, one can notice its changing landscape – construction is a constant and cranes dress the horizon. As of 2022, Toronto was home to 252 active cranes (dwarfing the 203 active cranes across the United States), and the majority of these were used for new builds rather than retrofitting older structures. According to heritage architect Catherine Nasmith, “it takes about 50 years of energy savings to pay down the debt to the environment created by the creation and transportation of construction materials”. On top of that, only 12% of waste from construction sites is diverted from landfill. The remaining 88% overwhelms landfills and accounts for 20–30% of the total municipal landfill in Ontario. A frightening prospect is that Ontario is expected to exceed its landfill capacity by 2032.

This building, 7 Labatt Ave, has lived a life longer than most of Toronto’s inhabitants. Over 110 years it has morphed with its tenants and now, it's slated for demolition. This exhibition is an ode to the building and others like it, an exploration of the impact of construction in this city and the value we place on overlooked and discarded things. What would Toronto look like if we opted to retrofit buildings before demolishing them? How could our value system shift to appreciate the unique heritage of the city?

Stats pertaining to the construction industry in Toronto

Exhibit

The artifacts in this exhibition are cast with a mixture of 50–75% collected debris from construction sites around Toronto, including famous landmarks, ignored structures and Victorian houses. The binding component of the mixture is gypsum based, which is a material commonly used in the construction of drywall, plaster and sometimes cement.

The molds used to cast the structures were created from offcut insulation boards salvaged from construction sites and their shapes often dictate the final form of the sculpture. Architectural and abstract in their form, they could live in centuries past or future, in an imagined city built on the foundation of its past and quietly carrying its hidden histories within its walls.

HISTORY

In the early 1900s, the land on which 7 Labatt Ave (formerly Radenhurst St) stands was housing. The business and manufacturing on this street began with a manufacturer of metallic conduit and interior decorations at 33 Labatt Ave. By the early 1910s, the housing was gone and a building was erected which spanned plots 11–21 Labatt Ave. (This building was the original structure of the current 7 Labatt Ave). At the time the original structure was built, the John Labatt Brewing Company had expanded its operations to Toronto and this building was the site of one of its bottling plants.

By 1917, the building had expanded from plots 11–21 to 7–21. In 1917, the Crouse-Hinds Company, manufacturers of electrical specialities, signed a lease with John Labatt Limited to rent plots 7–21 for $458.33 per month. Crouse-Hinds left the building in the mid 1960s, making them one of the longest term tenants of the building’s history.

In the 1920s, the company specialized in industrial lighting and traffic signals and in 1925, they manufactured and installed Toronto’s first traffic light at Yonge and Bloor.

According to research and records, 7 Labatt Ave was vacant from 1992–1994. Presumably this was for renovation to launch 7 Labatt Place in 1995, a community of professional, business-minded individuals.

In 2013, Labatt Urban Village was announced to replace the current building. It would be a 413 foot-high building atop an 11 storey podium.

Images, newspaper clippings, books and other historical items.

Timeline of the 110 year history of tenants in the building.

experience

The exhibit featured 3 die-cast and green enamel explosion proof lights that were manufactured in this building by the Crouse-Hinds company while their factory was in the building.

The sound playing throughout the exhibit was an abstracted drone I made from a recording of a construction site.

ONTARIO SCIENCE CENTRE

As part of the Architectural Conservancy of Ontario's annual symposium, the exhibit was displayed at the historic Ontario Science Centre. The centre was built by Japanese Canadian architect Raymond Moriyama, and as of the exhibit, was in a state of limbo as the provinces government has proposed a plan to demolish it (more on this).

The centre is integrated into the one of the hills of the Don Valley ravine and sits 6km north of the Don Valley Brickworks, the where most of the bricks used in this project were made in the early 20th century.

Designer, Artist

Creator, Designer

For over 2 decades I have worked for a vast array of clients across North America, creating digital + print work, objects, and merchandise collected around the world.

A label focused on experimental, environmentally based, very limited objects through sustainable material exploration and collaboration with musicians and artists.

Collective

Musician

A non-profit located on the arid coast of Almeria, Spain. Its site has inspired numerous projects that: defend the ocean, resolve environmental plastics, equilibrate agriculture and prevent desertification. It serves to function with the purpose of scientific research, design and reporting through the collaboration of respected experts.

I record music, scores, soundtracks, and field recordings for art exhibitions, films, and personal exploration. For the most part, Extempore is a mostly improvised analog process capturing sonic moments in time.

Designer, Artist

For over 2 decades I have worked for a vast array of clients across North America, creating digital + print work, objects, and merchandise collected around the world.

Creator, Designer

A label focused on experimental, environmentally based, very limited objects through sustainable material exploration and collaboration with musicians and artists.

Collective

A non-profit located on the arid coast of Almeria, Spain. Its site has inspired numerous projects that: defend the ocean, resolve environmental plastics, equilibrate agriculture and prevent desertification. It serves to function with the purpose of scientific research, design and reporting through the collaboration of respected experts.

Musician

I record music, scores, soundtracks, and field recordings for art exhibitions, films, and personal exploration. For the most part, Extempore is a mostly improvised analog process capturing sonic moments in time.